In his novel, James Clavell calls Changi; Genesis: Beginning again. These men have indeed encountered rebirth. Dealing with incarceration in a Japanese prison camp, King Rat (showing on TCM 2-21) holds none of the usual clichés of a WWII P.O.W. film. There are no escape attempts, uprisings, or flag flying patriotism scenes here. Instead, we see real men gnawed by hunger, physically broken, and fighting to retain their sanity.

1945. Flanked by the sea on one side and surrounded by deep jungle, Changi is an isolated camp on the eastern coast of Singapore. There is nowhere to run. The Japanese control the men mainly through starvation and lack of medical attention. Rule of the camp is left to those inside the wire with British, Australian, and American officers in charge of their own men. The death rate is high.

One man, a nameless American corporal, seems to have the best of everything. Through shrewd cunning and trade, “The King” as he is known, has become the wealthiest man in the camp. Provost Marshall Robin Grey, is sure that the corporal’s riches come at the expense of others, and is determined to see justice done. The two begin a game of cat and mouse, but we’re never sure which is predator or prey. Entering this personal war is Flight Lt. Peter Marlowe. An upper class Brit, Marlowe is first valued by the King as an interpreter who could help his trading abilities with the Japanese guards. As time wears on and the two men gain respect for each other, Marlowe must make moral choices between what he’s been taught about honesty and fair play vs. survival.

Although Clavell had written a best selling novel, many of the situations and storyline of King Rat were un-filmable under the Hays code. Fortunately, Clavell was also an excellent screenwriter (To Sir With Love [1967], The Great Escape [1963]) and chose to adapt his own work for the film. While some parts of the book were excised for language, sexual content, and time constraints, King Rat comes to the screen very much intact regarding it’s message and intent. That many scenes, including overt homosexuality managed to escape the cutting room floor, is a credit to Clavell’s deft storytelling ability.

This is a very stylized picture, but it never loses its authenticity or drops the threads that hold its story together. Director Bryan Forbes utilizes many techniques popularized by the French New Wave. His use of freeze frames, quick cutting close ups, and superb camera movement, act as our eyes, drawing us into the camp and the lives of these men. Composer John Barry’s lyrical score adds a mournful quality, blending eastern and western instruments, and enhancing the moodiness of the film.

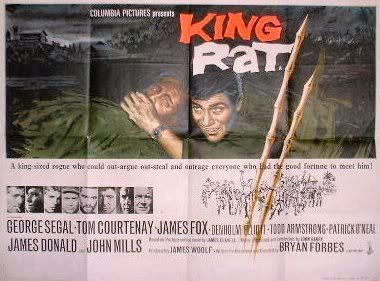

But it’s the great acting that makes this work live and breathe as few films ever have. George Segal as the King, gives the best performance of his career here in an understated tone, while Tom Courtenay (Grey) and James Fox (Marlowe) are vivid characters that walk wide emotional lines. Also, look for Patrick O’Neal as Max, playing a great supporting role. Although Clavell makes all these characters multidimensional and sympathetic, the entire cast interprets them with a heartbreaking realism rarely seen in motion pictures.

While King Rat can be appreciated purely as a war film, it deals with life on many different levels. Its focus is not actual war or escape, but individuals living under difficult circumstances and how they react within them. Are they adapting and changing their circumstances--or merely changed by them?

The movie also deals with class structure and political ideals in the three leads. The anonymous corporal is of the lowest rank, yet uses mettle to supercede all rank. Some might identify the King with the vermin of the film, but that’s much too easy an answer. His friendship with Marlowe is real—which is also the reason why it cannot remain as such when the war ends. Grey’s socialistic ideas of merit and seething hatred of class are pitted against his insecurity and inability to take individualistic stands—even when the cause is just.

Peter Marlowe is our touchstone, our identifying character. Unwilling to grovel, he is respected by the King. The American in turn, teaches him that a stiff upper lip cannot feed a hungry man or save his friends. Knowledge and ability are power and should be used as such. Does the King corrupt Marlowe’s nature? Or is he simply opening his eyes to the facts of life and the façade he’s been living under all these years?

It’s interesting to note that those who are deemed failures in society are the ones who flourish in the camp. Precisely because they exploit their abilities and know that life without respect is better than death--because they’ve never had respect to begin with. Steven, the homosexual nurse, is able to cadge cigarettes and all kinds of other things that would never be given to a heterosexual male. Also, his skills and compassion as a caretaker save lives and ease the suffering of many men. The King lives by a hustler’s street code that allowed him merely to survive on the outside, but here with the playing field leveled, he comes into his own. These two men (and others) teach Marlowe that all men are members of the human race, irrespective of class or background.

All in the camp make compromises. As Marlowe tells Grey, “We’re all liars. You’ve got to be a liar to stay alive.” But does the pressure cooker grind actually change a man’s nature—or bring out what was already inside him? King Rat seems to suggest the latter, and for many, the greatest terror is coming to terms with what lurks deep within. Corruption is everywhere and takes many forms, but as in everyday life, the truly diabolical are often the most self-righteous. Although maimed and scarred, physically and spiritually, these men have come to a new understanding of what life is, and the fuel that sustains it—be it food, camaraderie, faith, or pure hatred. Survival is not a matter of strength, but adaptability and mutation. Life is no longer just a heartbeat or pulse, but the ability to live in a cruel unconscionable world without being broken by despair. This is Genesis: Beginning again.