Gone With or Without fanfare

- Lzcutter

- Administrator

- Posts: 3149

- Joined: April 12th, 2007, 6:50 pm

- Location: Lake Balboa and the City of Angels!

- Contact:

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

Chuck Yeager: Hey, Ridley, ya got any Beeman's?

Jack Ridley: Yeah, I think I got me a stick.

Chuck Yeager: Loan me some, will ya? I'll pay ya back later.

Jack Ridley: Fair enough.

Sam Shepard and Levon Helm, The Right Stuff

His voice sounded like gravel but as part of The Band, he sang sweetly on numerous songs including The Weight, Up on Cripple Creek and probably most famously, The Night They Drove Ol' Dixie Down

Musician and actor Levon Helm has died following a long, brave battle with cancer.

From the Hollywood Reporter:

Levon Helm, whose Arkansas country voice and tight-knit work on a spare drum kit helped transform one of music’s most renowned backing bands into The Band, has died after a long battle with cancer. He was 71.

Helm died Thursday, April 19 in Woodstock, N.Y., Rolling Stone reports, where he built a recording studio attached to his home. In the Barn, he hosted a series of intimate “Midnight Ramble” concerts to raise money for medical bills and to resume performing after he was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1998.

“Thank you fans and music lovers who have made his life so filled with joy and celebration,” his daughter, Amy, and his wife, Sandy, said Tuesday in a statement thanking fans for their prayers. “He has loved nothing more than to play, to fill the room up with music, lay down the back beat and make the people dance. He did it every time he took the stage.”

With the rail-thin Helm as its backbone, The Band turned out such Americana hits as “The Weight,” “The Night They Drove Dixie Down,” “Up on Cripple Creek” (all with lead vocals by Helm), “Ophelia” and "Evangeline,” on which Helm played mandolin.

Other early favorites with Helm singing include “Chest Fever,” “Rag Mama Rag” and “Jemima Surrender.”

The fivesome turned out six studio albums in its prime before ending things with The Last Waltz, a concert staged on Thanksgiving Day 1976 at the Winterland ballroom in San Francisco. The all-star farewell show was turned into a documentary by Martin Scorsese.

The son of a cotton farmer, Helm at age 17 joined The Hawks, a rockabilly band fronted by Ronnie Hawkins that was popular in the American south and Canada. When the group moved its home base to Toronto, Helm and Hawkins recruited an all-Canadian lineup of musicians to join them: guitarist Robbie Robertson, bassist Rick Danko, pianist Richard Manuel and organist Garth Hudson (though everyone played many instruments).

After splitting with Hawkins in summer 1963 and playing gigs in bars throughout Canada, Texas and the Jersey Shore, The Hawks were asked by Bob Dylan — now looking for an electric sound — to serve as his backing band. The public, however, was not immediately happy with Dylan’s change of pace away from folk music, and a disenchanted Helm quit the music business for two years, working on an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico.

After The Hawks toured with Dylan in 1966, Helm came back into the fold. Amid the laid-back atmosphere of the Catskill Mountains in Woodstock, Dylan and the musicians now going by the name The Band played daily (the sessions would years later produce the Dylan-Band album The Basement Tapes).

During this period, The Band began writing their own songs and were encouraged to go off on their own by Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman. They signed with Capitol Records, which released The Band’s 1968 breakthrough album, Music From Big Pink. The influential LP — said to have persuaded Eric Clapton to leave Cream and head in a different direction — featured five distinct individual voices and instruments in a blend of country, folk, classical, R&B and soul.

Their sophomore effort, 1969’s The Band, was a critical and commercial hit that included “The Night They Drove Dixie Down,” and 1970’s Stage Fright featured “The Shape I’m In.” Cahoots (1971), with “Life Is a Carnival,” followed as tension between Helm and Robertson over control of the group increased.

After The Last Waltz, Helm did the first of three solo albums, Levon Helm & the RCO All Stars. The Band reformed in 1983 without Robertson, and following Manuel's 1986 suicide, the remaining trio released 1993's Jericho, recorded at Helm's home studio. Danko died in 1999, and the group broke up for good.

The Band entered the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994 and received the Grammys’ Lifetime Achievement Award in 2008. At the latest Hall of Fame induction ceremony April 14, Robertson offered his “prayers and love” for the drummer.

Throat cancer and radiation treatments reduced Helm’s once-powerful tenor to a whisper, but his voice grew stronger in the ensuing years and he soldiered on. During production of 2007’s folk album Dirt Farmer — a Grammy winner and his first solo album in a quarter-century — he estimated that his singing voice was 80 percent recovered.

Two subsequent albums, 2009’s Electric Dirt and last year’s Ramble at the Ryman, also collected Grammys.

Helm also had a career as an actor. He made his film debut in Coal Miner’s Daughter (1980), playing the father of Loretta Lynn, and he performed Bill Monroe's “Blue Moon of Kentucky” on the soundtrack. He also had roles in The Right Stuff (1983), The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (2005), Shooter (2007) and In the Electric Mist (2009).

Helm leaves behind Sandy, his wife of 30 years, and their daughter, Amy, a vocalist and instrumentalist who recorded with her father.

[youtube][/youtube]

Jack Ridley: Yeah, I think I got me a stick.

Chuck Yeager: Loan me some, will ya? I'll pay ya back later.

Jack Ridley: Fair enough.

Sam Shepard and Levon Helm, The Right Stuff

His voice sounded like gravel but as part of The Band, he sang sweetly on numerous songs including The Weight, Up on Cripple Creek and probably most famously, The Night They Drove Ol' Dixie Down

Musician and actor Levon Helm has died following a long, brave battle with cancer.

From the Hollywood Reporter:

Levon Helm, whose Arkansas country voice and tight-knit work on a spare drum kit helped transform one of music’s most renowned backing bands into The Band, has died after a long battle with cancer. He was 71.

Helm died Thursday, April 19 in Woodstock, N.Y., Rolling Stone reports, where he built a recording studio attached to his home. In the Barn, he hosted a series of intimate “Midnight Ramble” concerts to raise money for medical bills and to resume performing after he was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1998.

“Thank you fans and music lovers who have made his life so filled with joy and celebration,” his daughter, Amy, and his wife, Sandy, said Tuesday in a statement thanking fans for their prayers. “He has loved nothing more than to play, to fill the room up with music, lay down the back beat and make the people dance. He did it every time he took the stage.”

With the rail-thin Helm as its backbone, The Band turned out such Americana hits as “The Weight,” “The Night They Drove Dixie Down,” “Up on Cripple Creek” (all with lead vocals by Helm), “Ophelia” and "Evangeline,” on which Helm played mandolin.

Other early favorites with Helm singing include “Chest Fever,” “Rag Mama Rag” and “Jemima Surrender.”

The fivesome turned out six studio albums in its prime before ending things with The Last Waltz, a concert staged on Thanksgiving Day 1976 at the Winterland ballroom in San Francisco. The all-star farewell show was turned into a documentary by Martin Scorsese.

The son of a cotton farmer, Helm at age 17 joined The Hawks, a rockabilly band fronted by Ronnie Hawkins that was popular in the American south and Canada. When the group moved its home base to Toronto, Helm and Hawkins recruited an all-Canadian lineup of musicians to join them: guitarist Robbie Robertson, bassist Rick Danko, pianist Richard Manuel and organist Garth Hudson (though everyone played many instruments).

After splitting with Hawkins in summer 1963 and playing gigs in bars throughout Canada, Texas and the Jersey Shore, The Hawks were asked by Bob Dylan — now looking for an electric sound — to serve as his backing band. The public, however, was not immediately happy with Dylan’s change of pace away from folk music, and a disenchanted Helm quit the music business for two years, working on an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico.

After The Hawks toured with Dylan in 1966, Helm came back into the fold. Amid the laid-back atmosphere of the Catskill Mountains in Woodstock, Dylan and the musicians now going by the name The Band played daily (the sessions would years later produce the Dylan-Band album The Basement Tapes).

During this period, The Band began writing their own songs and were encouraged to go off on their own by Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman. They signed with Capitol Records, which released The Band’s 1968 breakthrough album, Music From Big Pink. The influential LP — said to have persuaded Eric Clapton to leave Cream and head in a different direction — featured five distinct individual voices and instruments in a blend of country, folk, classical, R&B and soul.

Their sophomore effort, 1969’s The Band, was a critical and commercial hit that included “The Night They Drove Dixie Down,” and 1970’s Stage Fright featured “The Shape I’m In.” Cahoots (1971), with “Life Is a Carnival,” followed as tension between Helm and Robertson over control of the group increased.

After The Last Waltz, Helm did the first of three solo albums, Levon Helm & the RCO All Stars. The Band reformed in 1983 without Robertson, and following Manuel's 1986 suicide, the remaining trio released 1993's Jericho, recorded at Helm's home studio. Danko died in 1999, and the group broke up for good.

The Band entered the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994 and received the Grammys’ Lifetime Achievement Award in 2008. At the latest Hall of Fame induction ceremony April 14, Robertson offered his “prayers and love” for the drummer.

Throat cancer and radiation treatments reduced Helm’s once-powerful tenor to a whisper, but his voice grew stronger in the ensuing years and he soldiered on. During production of 2007’s folk album Dirt Farmer — a Grammy winner and his first solo album in a quarter-century — he estimated that his singing voice was 80 percent recovered.

Two subsequent albums, 2009’s Electric Dirt and last year’s Ramble at the Ryman, also collected Grammys.

Helm also had a career as an actor. He made his film debut in Coal Miner’s Daughter (1980), playing the father of Loretta Lynn, and he performed Bill Monroe's “Blue Moon of Kentucky” on the soundtrack. He also had roles in The Right Stuff (1983), The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (2005), Shooter (2007) and In the Electric Mist (2009).

Helm leaves behind Sandy, his wife of 30 years, and their daughter, Amy, a vocalist and instrumentalist who recorded with her father.

[youtube][/youtube]

Lynn in Lake Balboa

"Film is history. With every foot of film lost, we lose a link to our culture, to the world around us, to each other and to ourselves."

"For me, John Wayne has only become more impressive over time." Marty Scorsese

Avatar-Warner Bros Water Tower

"Film is history. With every foot of film lost, we lose a link to our culture, to the world around us, to each other and to ourselves."

"For me, John Wayne has only become more impressive over time." Marty Scorsese

Avatar-Warner Bros Water Tower

- JackFavell

- Posts: 11926

- Joined: April 20th, 2009, 9:56 am

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

What the heck is going on today?

I'll really miss Levon Helm. We just saw him in November, still laying down that back beat.

My sister used to run home to watch Dark Shadows, and I caught the bug from her, though I really had no idea what was going on. As far as I'm concerned Jonathan Frid WAS the show. I used to love the scenes between him and Angelique.

I'll really miss Levon Helm. We just saw him in November, still laying down that back beat.

My sister used to run home to watch Dark Shadows, and I caught the bug from her, though I really had no idea what was going on. As far as I'm concerned Jonathan Frid WAS the show. I used to love the scenes between him and Angelique.

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

I wasn't a big DARK SHADOWS person. But I remember at least two recordings of music from the show. "Quentin's Theme" and another tune. Pretty instrumentals.

- moira finnie

- Administrator

- Posts: 8024

- Joined: April 9th, 2007, 6:34 pm

- Location: Earth

- Contact:

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

The beautiful British-born actress, Patricia Medina has died at age 92. If a script called for a stylish minx, the often mischievous-looking, brown--eyed, brown-haired Medina could look at home on the bounding main in pirate gear, kittenish in a harem, mysterious in a trench coat surrounded by fog and completely sophisticated in a Park Avenue setting. Never quite a star, but a leading lady for decades, she projected intelligence and humor as well as poise in her long career despite the vicissitudes of movie roles, which included appearances in the distinguished company of both Orson Welles in Mr. Arkadin (1951) as well as Moe, Larry and Curly Joe in Snow White and the Three Stooges (1961). Off-screen, she was married to actors Richard Greene before WWII and later was very happily wed to Joseph Cotten. Ms. Medina also wrote a highly entertaining, frothy autobiography, "Laid Back in Hollywood". (She sounds like fun). Below is her obit from the LA Times:

Patricia Medina dies at 92; Briton was '50s Hollywood leading lady

Patricia Medina began her film career in her native England in the 1930s and after World War II arrived in L.A., where she was initially signed to MGM. In 1960, she married Joseph Cotten.

By Dennis McLellan, Los Angeles Times

May 2, 2012

Advertisement

Patricia Medina, a British-born actress whose Hollywood career as a leading lady in the 1950s spanned the talking mule comedy "Francis" and Orson Welles' crime-thriller "Mr. Arkadin," has died. She was 92.

Medina, the widow of actor Joseph Cotten, died Saturday at Barlow Respiratory Hospital in Los Angeles, said Meredith Silverbach, a close friend. She had been in declining health.

A petite, dark-haired beauty who launched her film career in England in the late 1930s, Medina was married to actor Richard Greene when she arrived in Hollywood after World War II.

"She was a stunning woman," said Silverbach. "In her youth, they called her 'the most beautiful face in England.' "

Initially signed to MGM, Medina went on to play leads in movies such as "Abbott and Costello in the Foreign Legion" (1950), "Sangaree" with Fernando Lamas (1953), "Plunder of the Sun" with Glenn Ford (1953), "Botany Bay" with Alan Ladd (1953) and "Phantom of the Rue Morgue" with Karl Malden (1954).

She also played opposite Louis Hayward in the early '50s adventure films "Fortunes of Captain Blood," "The Lady and the Bandit," "Lady in the Iron Mask" and "Captain Pirate."

Medina and Greene were divorced in 1951. In 1960, in a ceremony at the home of David O. Selznick and Jennifer Jones, she married the widowed Cotten, who had made his feature film debut in Welles' 1941 classic "Citizen Kane."

They appeared in a number of stage productions together, and Medina made her Broadway debut in 1962 in "Calculated Risk," starring Cotten, who died in 1994.

They were "blissfully devoted to one another," United Press International Hollywood reporter Vernon Scott wrote in 2000.

"Medina and Cotten were a curious pair," Scott wrote. "She is a vivacious extrovert. Cotton was a gentlemanly Virginian, a quiet, considerate man.

"At myriad parties and industry events they were inseparable, among the most popular couples in town. They represented stability in this socially unstable community."

One of three sisters whose mother was English and father was Spanish, Medina was born in England on July 19, 1919, and grew up in Stanmore, about an hour from London. She spent a number of years in Paris while growing up and was fluent in French, Italian and Spanish.

"In England I was nearly always cast as someone of mysterious origin, not too clearly designated but probably from some Southern European country," Medina told The Times in 1947. "Here they decided in my first film, 'The Secret Heart,' that I should be a Yankee. In my second I'm definitely English. It's all rather confusing, I must say."

She met Greene while they were working at the same studio in England, and they married in 1941. They later co-starred in the 1944 romantic comedy "Don't Take It to Heart" and appeared together in the 1949 film "The Fighting O'Flynn."

Medina, who lived in Westwood, wrote the 1998 autobiography "Laid Back in Hollywood."

She had no immediate survivors.

-

Vecchiolarry

- Posts: 1392

- Joined: May 6th, 2007, 10:15 pm

- Location: Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

Dear Moira,

Thank you for informing us about Patricia Medina. It is unfortunate that she has died, as I thought she could be a good guest for next years TCM Film Festival. She certainly was an intelligent raconteur, and a very humourous one.

At a dinner party, given by Louise Fazenda and Hal Wallis in 1961(shortly before Louise was murdered), I met her & Joseph Cotton. I sat beside her and Joseph opposite down the table.

Agnes Moorehead sat opposite me.

PM urged Joseph to tell us all about the time he kicked Hedda Hopper in the ass!!! And, he did!! She whispered to me and Agnes, "I like to stir things up at these things!!"...

I have always thought and have post here somewhere (?) that if there'd been no Hedy Lamarr, Vivien Leigh nor Joan Bennett, then Patricia Medina would have had a bigger career..

She remained a good friend of Lana Turner, after both appeared in "The Three Musketeers" in 1948...

Larry

Thank you for informing us about Patricia Medina. It is unfortunate that she has died, as I thought she could be a good guest for next years TCM Film Festival. She certainly was an intelligent raconteur, and a very humourous one.

At a dinner party, given by Louise Fazenda and Hal Wallis in 1961(shortly before Louise was murdered), I met her & Joseph Cotton. I sat beside her and Joseph opposite down the table.

Agnes Moorehead sat opposite me.

PM urged Joseph to tell us all about the time he kicked Hedda Hopper in the ass!!! And, he did!! She whispered to me and Agnes, "I like to stir things up at these things!!"...

I have always thought and have post here somewhere (?) that if there'd been no Hedy Lamarr, Vivien Leigh nor Joan Bennett, then Patricia Medina would have had a bigger career..

She remained a good friend of Lana Turner, after both appeared in "The Three Musketeers" in 1948...

Larry

-

feaito

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

Patricia Medina was indeed a great beauty. RIP.

Larry, I did not know that Louise Fazenda was murdered.

Larry, I did not know that Louise Fazenda was murdered.

- Professional Tourist

- Posts: 1671

- Joined: March 1st, 2009, 7:12 pm

- Location: NYC

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

Thomas Mitchell, AM, Joseph Cotten, and Patricia Medina take a break from rehearsing the new play "Prescription: Murder," January 1962.

RIP Miss Medina.

- Sue Sue Applegate

- Administrator

- Posts: 3404

- Joined: April 14th, 2007, 8:47 pm

- Location: Texas

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

feaito, and professional tourist, I love that photo too!

So spur of the moment! Thanks.

So spur of the moment! Thanks.

Blog: http://suesueapplegate.wordpress.com/

Twitter:@suesueapplegate

TCM Message Boards: http://forums.tcm.com/index.php?/topic/ ... ue-sue-ii/

Sue Sue : https://www.facebook.com/groups/611323215621862/

Thelma Ritter: Hollywood's Favorite New Yorker, University Press of Mississippi-2023

Avatar: Ginger Rogers, The Major and The Minor

Twitter:@suesueapplegate

TCM Message Boards: http://forums.tcm.com/index.php?/topic/ ... ue-sue-ii/

Sue Sue : https://www.facebook.com/groups/611323215621862/

Thelma Ritter: Hollywood's Favorite New Yorker, University Press of Mississippi-2023

Avatar: Ginger Rogers, The Major and The Minor

- Lzcutter

- Administrator

- Posts: 3149

- Joined: April 12th, 2007, 6:50 pm

- Location: Lake Balboa and the City of Angels!

- Contact:

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

Actor George Lindsay probably best known for his role as Goober Pyle, cousin to that Southern sage, Gomer, has passed away:

From the Huffington Post:

George Lindsey, who spent nearly 30 years as the grinning Goober on "The Andy Griffith Show" and "Hee Haw," has died. He was 83.

A press release from Marshall-Donnelly-Combs Funeral Home in Nashville said Lindsay died early Sunday morning after a brief illness. Funeral arrangements were still being made.

Lindsey was the beanie-wearing Goober on "The Andy Griffith Show" from 1964 to 1968 and its successor, "Mayberry RFD," from 1968 to 1971. He played the same jovial character – a service station attendant – on "Hee Haw" from 1971 until it went out of production in 1993.

"America has grown up with me," Lindsey said in an Associated Press interview in 1985. "Goober is every man; everyone finds something to like about ol' Goober."

He joined "The Andy Griffith Show" in 1964 when Jim Nabors, portraying Gomer Pyle, left the program. Goober Pyle, who had been mentioned on the show as Gomer's cousin, thus replaced him.

"At that time, we were the best acting ensemble on TV. The scripts were terrific. Andy is the best script constructionist I've ever been involved with. And you have to lift your acting level up to his; he's awfully good."

Although he was best known as Goober, Lindsey had other roles during a long TV career. Earlier, he often was a "heavy" and once shot Matt Dillon on "Gunsmoke."

His other TV credits included roles on "M(asterisk)A(asterisk)S(asterisk)H," "The Wonderful World of Disney," "CHIPs," "The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour," "The Real McCoys," "Rifleman," "The Alfred Hitchcock Hour," "Twilight Zone" and "Love American Style."

Reflecting on his career, he said in 1985: "There's a residual effect of knowing I've made America laugh. I'm not the only one, but I've contributed something."

He had movie roles, too, appearing in "Cannonball Run II" and "Take This Job and Shove It." His voice was used in animated Walt Disney features including "The Aristocats," "The Rescuers" and "Robin Hood."

Lindsey was born in Jasper, Ala., the son of a butcher. He received a bachelor of science degree from Florence State Teachers College (now the University of North Alabama) in 1952 after majoring in physical education and biology and playing quarterback on the football team.

After spending three years in the Air Force, he worked one year as a high school baseball and basketball coach and history teacher near Huntsville, Ala.

In 1956, he attended the American Theatre Wing in New York City and began his professional career on Broadway, appearing in the musicals "All American" and "Wonderful Town."

He moved to Hollywood in the early 1960s and then to Nashville in the early 1990s.

"There's no place in the United States I can go that they don't know me. They may not know me, but they know the character," he told The Tennessean in 1980.

At that time, he said the Griffith show "was the first soft rural comedy with a moral."

"We physically and mentally became those people when we got to the set."

He did some standup comedy – ending the show by tap and break dancing.

One of his jokes:

"A football coach, holding a football, asks his quarterback, `Son, can you pass this?' The player says, `Coach, I don't even think I can swallow it.'"

Lindsey devoted much of his spare time to raising funds for the Alabama Special Olympics. For 17 years, he sponsored a celebrity golf tournament in Montgomery, Ala., that raised money for the mentally disabled.

The University of North Alabama awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1992, and he was affectionately called "Doctor Goober" by acquaintances after that.

From the Huffington Post:

George Lindsey, who spent nearly 30 years as the grinning Goober on "The Andy Griffith Show" and "Hee Haw," has died. He was 83.

A press release from Marshall-Donnelly-Combs Funeral Home in Nashville said Lindsay died early Sunday morning after a brief illness. Funeral arrangements were still being made.

Lindsey was the beanie-wearing Goober on "The Andy Griffith Show" from 1964 to 1968 and its successor, "Mayberry RFD," from 1968 to 1971. He played the same jovial character – a service station attendant – on "Hee Haw" from 1971 until it went out of production in 1993.

"America has grown up with me," Lindsey said in an Associated Press interview in 1985. "Goober is every man; everyone finds something to like about ol' Goober."

He joined "The Andy Griffith Show" in 1964 when Jim Nabors, portraying Gomer Pyle, left the program. Goober Pyle, who had been mentioned on the show as Gomer's cousin, thus replaced him.

"At that time, we were the best acting ensemble on TV. The scripts were terrific. Andy is the best script constructionist I've ever been involved with. And you have to lift your acting level up to his; he's awfully good."

Although he was best known as Goober, Lindsey had other roles during a long TV career. Earlier, he often was a "heavy" and once shot Matt Dillon on "Gunsmoke."

His other TV credits included roles on "M(asterisk)A(asterisk)S(asterisk)H," "The Wonderful World of Disney," "CHIPs," "The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour," "The Real McCoys," "Rifleman," "The Alfred Hitchcock Hour," "Twilight Zone" and "Love American Style."

Reflecting on his career, he said in 1985: "There's a residual effect of knowing I've made America laugh. I'm not the only one, but I've contributed something."

He had movie roles, too, appearing in "Cannonball Run II" and "Take This Job and Shove It." His voice was used in animated Walt Disney features including "The Aristocats," "The Rescuers" and "Robin Hood."

Lindsey was born in Jasper, Ala., the son of a butcher. He received a bachelor of science degree from Florence State Teachers College (now the University of North Alabama) in 1952 after majoring in physical education and biology and playing quarterback on the football team.

After spending three years in the Air Force, he worked one year as a high school baseball and basketball coach and history teacher near Huntsville, Ala.

In 1956, he attended the American Theatre Wing in New York City and began his professional career on Broadway, appearing in the musicals "All American" and "Wonderful Town."

He moved to Hollywood in the early 1960s and then to Nashville in the early 1990s.

"There's no place in the United States I can go that they don't know me. They may not know me, but they know the character," he told The Tennessean in 1980.

At that time, he said the Griffith show "was the first soft rural comedy with a moral."

"We physically and mentally became those people when we got to the set."

He did some standup comedy – ending the show by tap and break dancing.

One of his jokes:

"A football coach, holding a football, asks his quarterback, `Son, can you pass this?' The player says, `Coach, I don't even think I can swallow it.'"

Lindsey devoted much of his spare time to raising funds for the Alabama Special Olympics. For 17 years, he sponsored a celebrity golf tournament in Montgomery, Ala., that raised money for the mentally disabled.

The University of North Alabama awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1992, and he was affectionately called "Doctor Goober" by acquaintances after that.

Lynn in Lake Balboa

"Film is history. With every foot of film lost, we lose a link to our culture, to the world around us, to each other and to ourselves."

"For me, John Wayne has only become more impressive over time." Marty Scorsese

Avatar-Warner Bros Water Tower

"Film is history. With every foot of film lost, we lose a link to our culture, to the world around us, to each other and to ourselves."

"For me, John Wayne has only become more impressive over time." Marty Scorsese

Avatar-Warner Bros Water Tower

- moira finnie

- Administrator

- Posts: 8024

- Joined: April 9th, 2007, 6:34 pm

- Location: Earth

- Contact:

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

I have to admit I liked George Lindsay's Goober much more than Gomer. There was something very sweet and funny about him. If others liked the Goob too you might enjoy seeing him in this clip, imitating Cary Grant (yes, you read that correctly). It starts around 4:39. "Goober never does miss a Cary Grant movie. He studies him..." And stick around for his Edward G. Robinson imitation.

[youtube][/youtube]

[youtube][/youtube]

- JackFavell

- Posts: 11926

- Joined: April 20th, 2009, 9:56 am

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

Goober! Oh, dear.

I felt just the same as you, Moira.. I liked Goober best of the Andy Griffith regulars, and I always enjoyed it when George Lindsay appeared on other shows. He was such an easy going presence. I'm gonna miss him very much.

I felt just the same as you, Moira.. I liked Goober best of the Andy Griffith regulars, and I always enjoyed it when George Lindsay appeared on other shows. He was such an easy going presence. I'm gonna miss him very much.

- moira finnie

- Administrator

- Posts: 8024

- Joined: April 9th, 2007, 6:34 pm

- Location: Earth

- Contact:

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

Thanks, JF--it's good to know that another Gooberhead is on the boards!

- moira finnie

- Administrator

- Posts: 8024

- Joined: April 9th, 2007, 6:34 pm

- Location: Earth

- Contact:

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

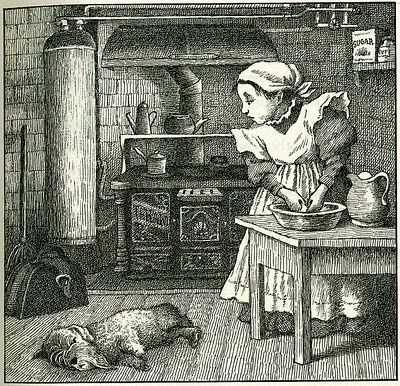

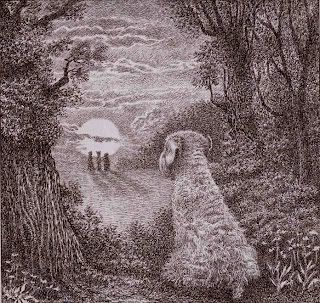

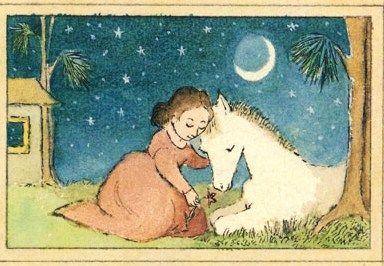

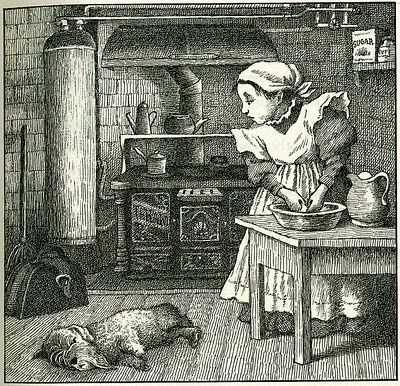

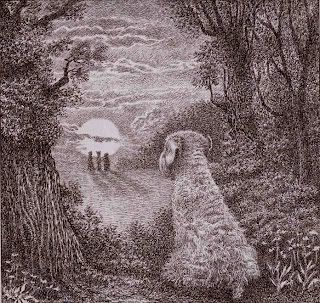

Little Bear off on his adventure to the moon, bidding his mother goodbye.

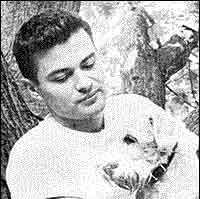

Goodbye to a man who feels as though he was a friend since childhood--illustrator and author Maurice Sendak has died at age 83. Though many of his most popular stories and drawings such as Where the Wild Things Are were too intense for me, others live in fond memory. One of my first books was Charlotte and the White Horse, which he illustrated for author Ruth Krauss and another was Else Holmelund Minarik's Little Bear, which he drew with great tenderness and considerable humor, along with many sequels. I've never forgotten the enchantment of either book. You can see this creative man's obituary from The New York Times below.

The cover illustration from Charlotte and the White Horse.

Below are the author's words from "Maurice Sendak: On Life, Death, and Children's Lit," an interview with Terri Gross on NPR's "Fresh Air" broadcast on September 20, 2011. You can hear this interview in its entirety here.From NYTimes, May 8, 2012:

Maurice Sendak, Author of Splendid Nightmares, Dies at 83

By MARGALIT FOX

Maurice Sendak, widely considered the most important children’s book artist of the 20th century, who wrenched the picture book out of the safe, sanitized world of the nursery and plunged it into the dark, terrifying and hauntingly beautiful recesses of the human psyche, died on Tuesday in Danbury, Conn. He was 83 and lived in Ridgefield, Conn.

The cause was complications from a recent stroke, said Michael di Capua, his longtime editor.

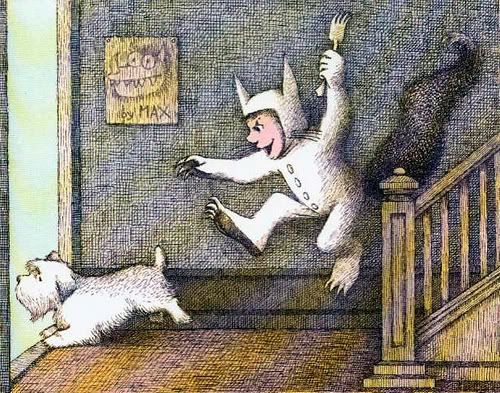

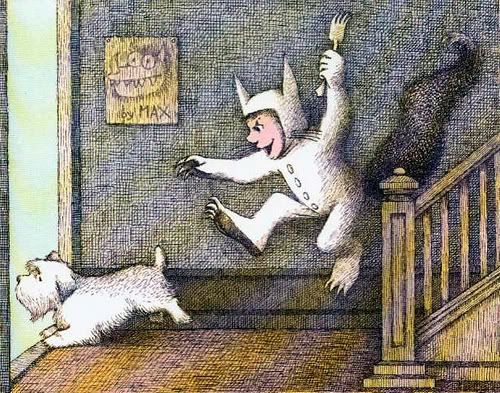

Roundly praised, intermittently censored and occasionally eaten, Mr. Sendak’s books were essential ingredients of childhood for the generation born after 1960 or thereabouts, and in turn for their children. He was known in particular for more than a dozen picture books he wrote and illustrated himself, most famously “Where the Wild Things Are,” which was simultaneously genre-breaking and career-making when it was published by Harper & Row in 1963.

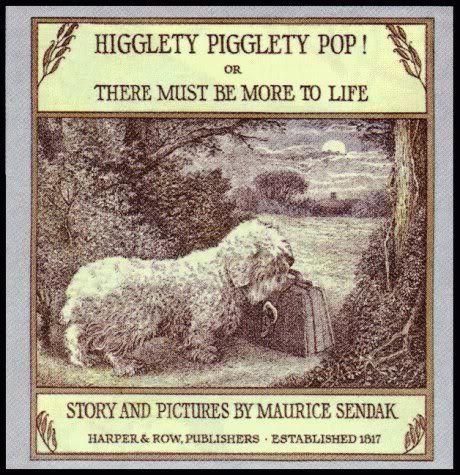

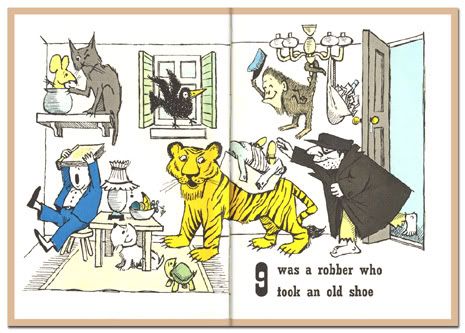

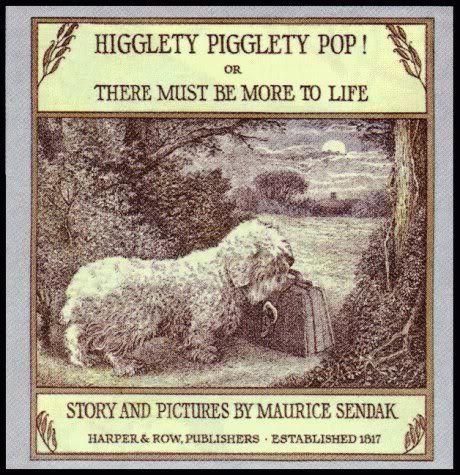

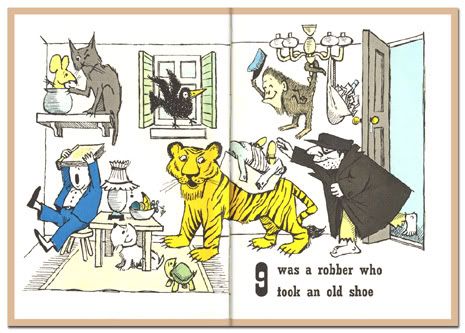

Among the other titles he wrote and illustrated, all from Harper & Row, are “In the Night Kitchen” (1970) and “Outside Over There” (1981), which together with “Where the Wild Things Are” form a trilogy; “The Sign on Rosie’s Door” (1960); “Higglety Pigglety Pop!” (1967); and “The Nutshell Library” (1962), a boxed set of four tiny volumes comprising “Alligators All Around,” “Chicken Soup With Rice,” “One Was Johnny” and “Pierre.”

In September, a new picture book by Mr. Sendak, “Bumble-Ardy” — the first in 30 years for which he produced both text and illustrations — was issued by HarperCollins Publishers. The book, which spent five weeks on the New York Times children’s best-seller list, tells the not-altogether-lighthearted story of an orphaned pig (his parents are eaten) who gives himself a riotous birthday party.

A posthumous picture book, “My Brother’s Book” — a poem written and illustrated by Mr. Sendak and inspired by his love for his late brother, Jack — is scheduled to be published next February.

Mr. Sendak’s work was the subject of critical studies and major exhibitions; in the second half of his career, he was also renowned as a designer of theatrical sets. His art graced the writing of other eminent authors for children and adults, including Hans Christian Andersen, Leo Tolstoy, Herman Melville, William Blake and Isaac Bashevis Singer.

In book after book, Mr. Sendak upended the staid, centuries-old tradition of American children’s literature, in which young heroes and heroines were typically well scrubbed and even better behaved; nothing really bad ever happened for very long; and everything was tied up at the end in a neat, moralistic bow.

Mr. Sendak’s characters, by contrast, are headstrong, bossy, even obnoxious. (In “Pierre,” “I don’t care!” is the response of the small eponymous hero to absolutely everything.) His pictures are often unsettling. His plots are fraught with rupture: children are kidnapped, parents disappear, a dog lights out from her comfortable home.

A largely self-taught illustrator, Mr. Sendak was at his finest a shtetl Blake, portraying a luminous world, at once lovely and dreadful, suspended between wakefulness and dreaming. In so doing, he was able to convey both the propulsive abandon and the pervasive melancholy of children’s interior lives.

His visual style could range from intricately crosshatched scenes that recalled 19th-century prints to airy watercolors reminiscent of Chagall to bold, bulbous figures inspired by the comic books he loved all his life, with outsize feet that the page could scarcely contain. He never did learn to draw feet, he often said.

In 1964, the American Library Association awarded Mr. Sendak the Caldecott Medal, considered the Pulitzer Prize of children’s book illustration, for “Where the Wild Things Are.” In simple, incantatory language, the book told the story of Max, a naughty boy who rages at his mother and is sent to his room without supper. A pocket Odysseus, Max promptly sets sail:

And he sailed off through night and day

and in and out of weeks

and almost over a year

to where the wild things are.

There, Max leads the creatures in a frenzied rumpus before sailing home, anger spent, to find his supper waiting.

As portrayed by Mr. Sendak, the wild things are deliciously grotesque: huge, snaggletoothed, exquisitely hirsute and glowering maniacally. He always maintained he was drawing his relatives — who, in his memory at least, had hovered like a pack of middle-aged gargoyles above the childhood sickbed to which he was often confined.

Maurice Bernard Sendak was born in Brooklyn on June 10, 1928; his father, Philip, was a dressmaker in the garment district of Manhattan. Family photographs show the infant Maurice, or Murray as he was then known, as a plump, round-faced, slanting-eyed, droopy-lidded, arching-browed creature — looking, in other words, exactly like a baby in a Maurice Sendak illustration. Mr. Sendak adored drawing babies, in all their fleshy petulance.

A frail child beset by a seemingly endless parade of illnesses, Mr. Sendak was reared, he said afterward, in a world of looming terrors: the Depression; the war; the Holocaust, in which many of his European relatives perished; the seemingly infinite vulnerability of children to danger. The kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932 he experienced as a personal torment: if that fair-haired, blue-eyed princeling could not be kept safe, what certain peril lay in store for him, little Murray Sendak, in his humble apartment in Bensonhurst?

An image from the Lindbergh crime scene — a ladder leaning against the side of a house — would find its way into “Outside Over There,” in which a baby is carried off by goblins.

As Mr. Sendak grew up — lower class, Jewish, gay — he felt permanently shunted to the margins of things. “All I wanted was to be straight so my parents could be happy,” he told The New York Times in a 2008 interview. “They never, never, never knew.”

His lifelong melancholia showed in his work, in picture books like “We Are All in the Dumps With Jack and Guy” (HarperCollins, 1993), a parable about homeless children in the age of AIDS. It showed in his habits. He could be dyspeptic and solitary, working in his white clapboard home in the deep Connecticut countryside with only Mozart, Melville, Mickey Mouse and his dogs for company.

It showed in his everyday interactions with people, especially those blind to the seriousness of his enterprise. “A woman came up to me the other day and said, ‘You’re the kiddie-book man!’ ” Mr. Sendak told Vanity Fair last year.“I wanted to kill her.”

But Mr. Sendak could also be warm and forthright, if not quite gregarious. He was a man of ardent enthusiasms — for music, art, literature, argument and the essential rightness of children’s perceptions of the world around them. He was also a mentor to a generation of younger writers and illustrators for children, several of whom, including Arthur Yorinks, Richard Egielski and Paul O. Zelinsky, went on to prominent careers of their own.

As far back as he could remember, Mr. Sendak had loved to draw. That and looking out the window had helped him pass the long hours in bed. While he was still in high school he worked part time for All-American Comics, filling in backgrounds for book versions of the “Mutt and Jeff” comic strip. His first professional illustrations were for a physics textbook, “Atomics for the Millions,” published in 1947.

In 1948, at 20, he took a job building window displays for F. A. O. Schwarz. Through the store’s children’s book buyer, he was introduced to Ursula Nordstrom, the distinguished editor of children’s books at Harper & Row. The meeting, the start of a long, fruitful collaboration, led to Mr. Sendak’s first children’s book commission: illustrating “The Wonderful Farm,” by Marcel Aymé, published in 1951.

Under Ms. Nordstrom’s guidance, Mr. Sendak went on to illustrate books by other well-known children’s authors, including several by Ruth Krauss, notably “A Hole Is to Dig” (1952), and Else Holmelund Minarik’s “Little Bear” series. The first title he wrote and illustrated himself, “Kenny’s Window,” published in 1956, was a moody, dreamlike story about a lonely boy’s inner life.

Mr. Sendak’s books were often a window into his own experience. “Higglety Pigglety Pop! Or, There Must Be More to Life” was a valentine to Jennie, his beloved Sealyham terrier, who died shortly before the book was published.

At the start of the story, Jennie, who has everything a dog could want — including “a round pillow upstairs and a square pillow downstairs” — packs her bags and sets off on her own, pining for adventure. She finds it on the stage of the World Mother Goose Theatre, where she becomes a leading lady. Every day, and twice on Saturdays, Jennie, who looks rather like a mop herself, eats a mop made out of salami. This makes her very happy.

“Hello,” Jennie writes in a satisfyingly articulate letter to her master. “As you probably noticed, I went away forever. I am very experienced now and very famous. I am even a star. ... I get plenty to drink too, so don’t worry.”

By contrast, the huge, flat, brightly colored illustrations of “In the Night Kitchen,” the story of a boy’s journey through a fantastic nocturnal cityscape, are a tribute to the New York of Mr. Sendak’s childhood, recalling the 1930s films and comic books he adored all his life. (The three bakers who toil in the night kitchen are the spit and image of Oliver Hardy.)

Mr. Sendak’s later books could be much darker. “Brundibar” (Hyperion, 2003), with text by the playwright Tony Kushner, is a picture book based on an opera performed by the children of the Theresienstadt concentration camp. The opera, also called “Brundibar,” had been composed in 1938 by Hans Krasa, a Czech Jew who later died in Auschwitz.

Reviewing the book in The New York Times Book Review, Gregory Maguire called it “a capering picture book crammed with melodramatic menace and comedy both low and grand.” He added: “In a career that spans 50 years and counting, as Sendak’s does, there are bound to be lesser works. ‘Brundibar’ is not lesser than anything.”

With Mr. Kushner, Mr. Sendak collaborated on a stage version of the opera, performed in 2006 at the New Victory Theater in New York.

Despite its wild popularity, Mr. Sendak’s work was not always well received. Some early reviews of “Where the Wild Things Are” expressed puzzlement and outright unease. Writing in Ladies’ Home Journal, the psychologist Bruno Bettelheim took Mr. Sendak to task for punishing Max:

“The basic anxiety of the child is desertion,” Mr. Bettelheim wrote. “To be sent to bed alone is one desertion, and without food is the second desertion.” (Mr. Bettelheim admitted that he had not actually read the book.)

“In the Night Kitchen,” which depicts its young hero, Mickey, in the nude, prompted many school librarians to bowdlerize the book by drawing a diaper over Mickey’s nether region.

But these were minority responses. Mr. Sendak’s other awards include the Hans Christian Andersen Award for Illustration, the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award and, in 1996, the National Medal of the Arts, presented by President Bill Clinton. Twenty-two of his titles have been named New York Times best illustrated books of the year.

Many of Mr. Sendak’s books had second lives on stage and screen. Among the most notable adaptations are the operas “Where the Wild Things Are” and “Higglety Pigglety Pop!” by the British composer Oliver Knussen, and Carole King’s “Really Rosie,” a musical version of “The Sign on Rosie’s Door,” which appeared on television as an animated special in 1975 and on the Off Broadway stage in 1980.

In 2009, a feature film version of “Where the Wild Things Are” — part live action, part animated — by the director Spike Jonze opened to favorable notices. (With Lance Bangs, Mr. Jonze also directed “Tell Them Anything You Want,” a documentary film about Mr. Sendak first broadcast on HBO that year.)

In the 1970s, Mr. Sendak began designing sets and costumes for adaptations of his own work and, eventually, the work of others. His first venture was Mr. Knussen’s “Wild Things,” for which Mr. Sendak also wrote the libretto. Performed in a scaled-down version in Brussels in 1980, the opera had its full premiere four years later, to great acclaim, staged in London by the Glyndebourne Touring Opera.

With the theater director Frank Corsaro, he also created sets for several venerable operas, among them Mozart’s “Magic Flute,” performed by the Houston Grand Opera in 1980, and Leos Janacek’s “Cunning Little Vixen” for the New York City Opera in 1981.

For the Pacific Northwest Ballet, Mr. Sendak designed sets and costumes for a 1983 production of Tchaikovsky’s “Nutcracker”; a film version was released in 1986.

Among Mr. Sendak’s recent books is his only pop-up book, “Mommy?,” published by Scholastic in 2006, with a scenario by Mr. Yorinks and paper engineering by Matthew Reinhart.

Mr. Sendak’s companion of a half-century, Eugene Glynn, a psychiatrist who specialized in the treatment of young people, died in 2007. No immediate family members survive.

Though he understood children deeply, Mr. Sendak by no means valorized them unconditionally. “Dear Mr. Sun Deck ...” he could drone with affected boredom, imitating the semiliterate forced-march school letter-writing projects of which he was the frequent, if dubious, beneficiary.

But he cherished the letters that individual children sent him unbidden, which burst with the sparks that his work had ignited.

“Dear Mr. Sendak,” read one, from an 8-year-old boy. “How much does it cost to get to where the wild things are? If it is not expensive, my sister and I would like to spend the summer there.”

“I’m not unhappy about becoming old . . .[it's] what must be. I only cry when I see my friends go before me. I don’t believe in an afterlife, but I do expect to see my brother again . . . like a dream life . . . but I am in love with the world. I look right now out the window of my studio--I see my trees, these beautiful beautiful maples. It is a blessing to get old, to find the time to do the things, to read the books, to listen to the music. I don’t think I’m rationalizing . . . this is all inevitable, I have no control over it. The wondrous feeling of coming into my own—it took a very long time. You could be talking to a crazy person.”

“I have heart trouble. I’m very sick. I have nothing but praise now really for my life. . . I’m not unhappy. I cry a lot because I miss people. They die and I can’t stop them. They leave me and I love them more. I’m in a very soft mood, you gather, because new people have died. It’s what I dread more than my isolation. . . . [young people] if they only knew how little I know. Oh, God, there are so many beautiful things in the world that I will have to leave when I die, but I am ready, I am ready, I am ready.”

“Although certainly I’ll go before you’ll go, so I won’t have to miss you. But I will cry my way all the way to the grave. . . . I wish you all good things. Live your life, live your life, live your life.”

- JackFavell

- Posts: 11926

- Joined: April 20th, 2009, 9:56 am

Re: Gone With or Without fanfare

I'm all broken up over this. That was a very moving tribute to a beloved man, though that word would probably not sit well with him were he to hear it. Sendak deserved all the praise. He was a brilliant illustrator and author, spinning a secret world only children really know and understand. We all felt like his co-conspirators when we read his books. He understood.

Even at a very young age, when I was first presented with a copy of The Nutshell Library, I was intrigued with Sendak's beloved dog, Jennie, who somehow sneaked into each book that Sendak wrote. Jennie always stands out, a little aloof, wiser than any human. Any page that had Jennie on it was my favorite, no matter what book it was. I didn't know she was based on a real life dog, but I knew she was special, had a place of honor. Through my love of her, I felt connected somehow to Sendak.

I still have my Nutshell Library, it is the only possession I have from childhood that has moved with me through my entire life.

A few months ago, Sendak appeared in probably the most hilarious episode of The Colbert Report ever filmed. As far as I know, he's the only guest who ever got the better of Colbert.

Rest in peace, Mr. Sendak, and bless you.

Even at a very young age, when I was first presented with a copy of The Nutshell Library, I was intrigued with Sendak's beloved dog, Jennie, who somehow sneaked into each book that Sendak wrote. Jennie always stands out, a little aloof, wiser than any human. Any page that had Jennie on it was my favorite, no matter what book it was. I didn't know she was based on a real life dog, but I knew she was special, had a place of honor. Through my love of her, I felt connected somehow to Sendak.

I still have my Nutshell Library, it is the only possession I have from childhood that has moved with me through my entire life.

A few months ago, Sendak appeared in probably the most hilarious episode of The Colbert Report ever filmed. As far as I know, he's the only guest who ever got the better of Colbert.

Rest in peace, Mr. Sendak, and bless you.